Just because we are psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and other mental health workers does not mean that we are free from emotional disorders of many types. In certain respects, it probably helps many of us in the field be better therapists. However, there is one caveat to this statement. It is only if we have used one of the many types of psychotherapy that we can be good therapists.

I want to suggest an idea that I have thought of many times: All mental health workers should undergo one of the types of psychotherapy before they can be licensed to practice.

All my life, I have struggled with something that has a name, but no single face. It’s called social anxiety disorder, also abbreviated as SAD. It has been with me since childhood, and although I have learned to live with it, it has always shaped the way I navigate the world.

Social anxiety is more than shyness. It is the quiet, yet sometimes overwhelming, fear that you don’t belong. It’s the gnawing worry that others are watching you, judging you, or finding you foolish. It’s the urge to hide even when nothing bad has happened, simply because your mind tells you something will.

When I was a young boy in elementary school, I avoided the other children. During lunch and recess, when others were laughing, shouting, and playing together in the schoolyard, I stood off to the side, watching but not joining. I didn’t feel part of it. I felt different. I felt like if I spoke, they would laugh at me. If I were to try to join, I would be rejected. And so I stayed silent and apart.

That fear never fully left me. Even when I became a therapist — even after decades of working in hospitals, clinics, and private practice, side by side with psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and patients — I still felt uneasy in social situations. I could listen with great care and help others face their pain, but when it came to unstructured gatherings, meetings, or even casual lunches with colleagues, I often felt anxious. I worried that I wouldn’t say the right thing, that I would seem odd or uninteresting, or that others could see through me and detect something was off.

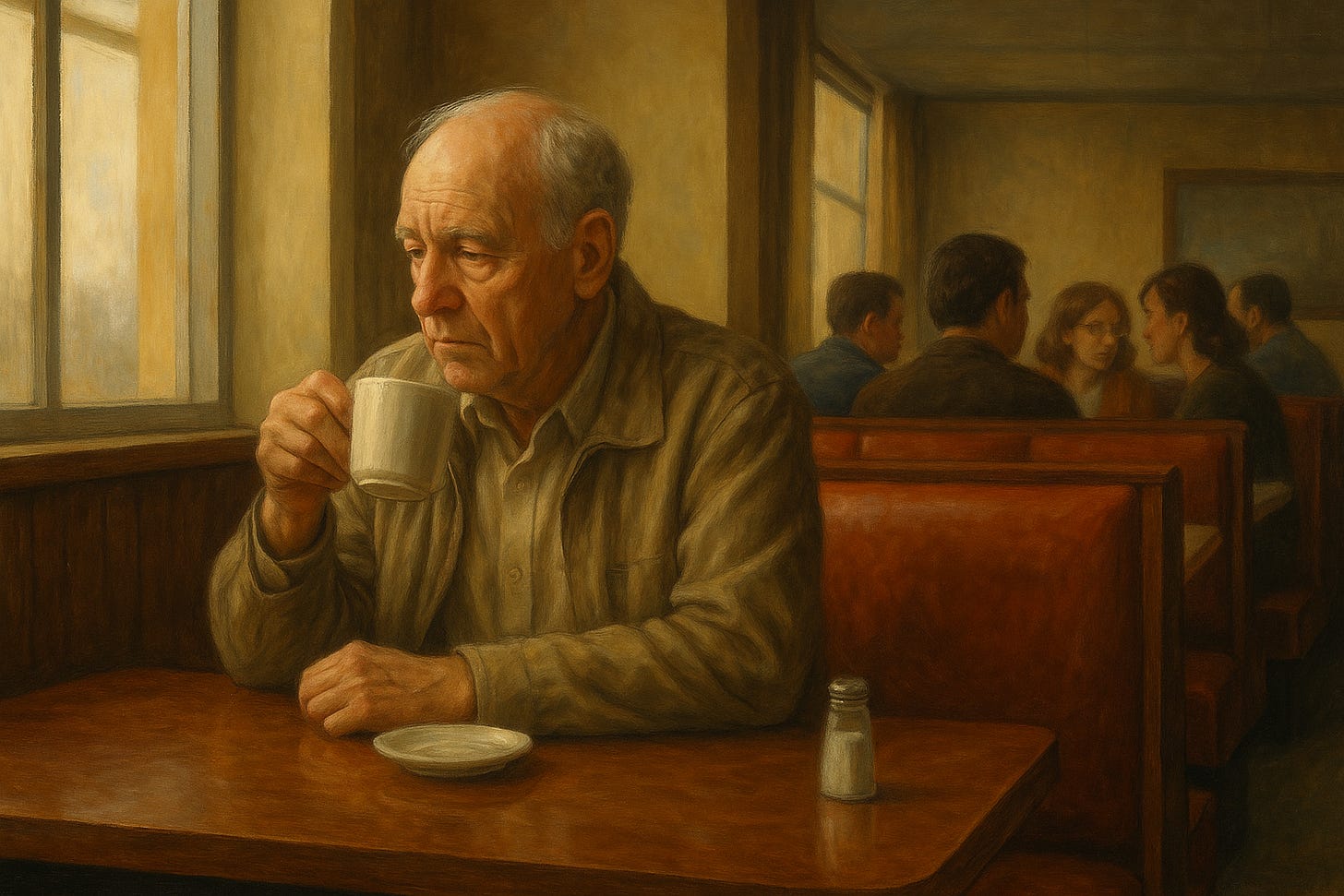

Now, at this stage of my life, I live in a senior community filled with good people. But even here, I feel that familiar discomfort. I go to breakfast each morning and sit with a small group of regulars I’ve come to appreciate. We talk, laugh, and share stories. But after breakfast, I retreat. I rarely attend lunch. I completely avoid dinner. I don’t go to most activities, even though some part of me wants to. It’s just that the fear creeps in — the fear of being judged, of being found lacking, of saying the wrong thing and being embarrassed. It is not rational, but it is powerful.

For those who have never experienced it, it can be hard to understand. Social anxiety doesn’t announce itself loudly. It whispers. It whispers that you’re not enough. It makes you sweat, tremble, or stumble over words when meeting someone new. It convinces you to stay home rather than risk the vulnerability of being seen.

It can lead you to relive every conversation, picking apart your words and worrying that you said too much, or too little, or nothing of value at all. It can leave you feeling alone even when surrounded by others.

There is help. Psychotherapy — especially group therapy — can make a real difference. When I was younger, group therapy gave me the chance to share my fears with others who understood them, and to realize I was not alone. Today, cognitive behavioral therapy has become a widely used and very effective treatment, helping people challenge the thoughts that feed their anxiety and gradually face the situations they fear. Sadly, that kind of therapy wasn’t available to me when I needed it most, but it exists now, and I hope more people find their way to it.

Social anxiety disorder doesn’t mean someone is broken. It means they are afraid. And often, behind that fear, there is a deep sensitivity, a longing to connect, and a well of kindness that hasn’t found the right bridge yet.

I’ve spent my life helping others heal. However, this is one area where I am still working on healing myself. And maybe, by writing this, I can offer a little healing to someone else who feels just as I’ve and who is hidden behind a wall, wishing to come out, and afraid of what might happen if they do.

“I want to suggest an idea that I have thought of many times: All mental health workers should undergo one of the types of psychotherapy before they can be licensed to practice”

Isn’t this a default requirement for psychotherapists? Back in my training that started in 2000 this was mainstream. I’m saddened to see that this has changed. I see many practitioners attempting to practice without doing their own work.

I loved this post. It made me feel less alone in my anxiety. You really managed to describe what social anxiety means for me - I’m not broken, I’m afraid of being seen.