I Years had been from Home (LIII. RETURNING.)

by Emily Dickinson

I years had been from home,

And now, before the door,

I dared not open, lest a face

I never saw before

Stare vacant into mine

And ask my business there.

My business, — just a life I left,

Was such still dwelling there?

I fumbled at my nerve,

I scanned the windows near;

The silence like an ocean rolled,

And broke against my ear.

I laughed a wooden laugh

That I could fear a door,

Who danger and the dead had faced,

But never quaked before.

I fitted to the latch

My hand, with trembling care,

Lest back the awful door should spring,

And leave me standing there.

I moved my fingers off

As cautiously as glass,

And held my ears, and like a thief

Fled gasping from the house.

Returning home after many years away sounds like a happy moment. But, Emily Dickinson's poem "I Years Had Been from Home" tells a very different story. Instead of joy and nostalgia, she gives us fear, hesitation, and even a bit of dread. It's the kind of feeling that makes you wonder if it is really home, if it doesn't feel the same anymore.

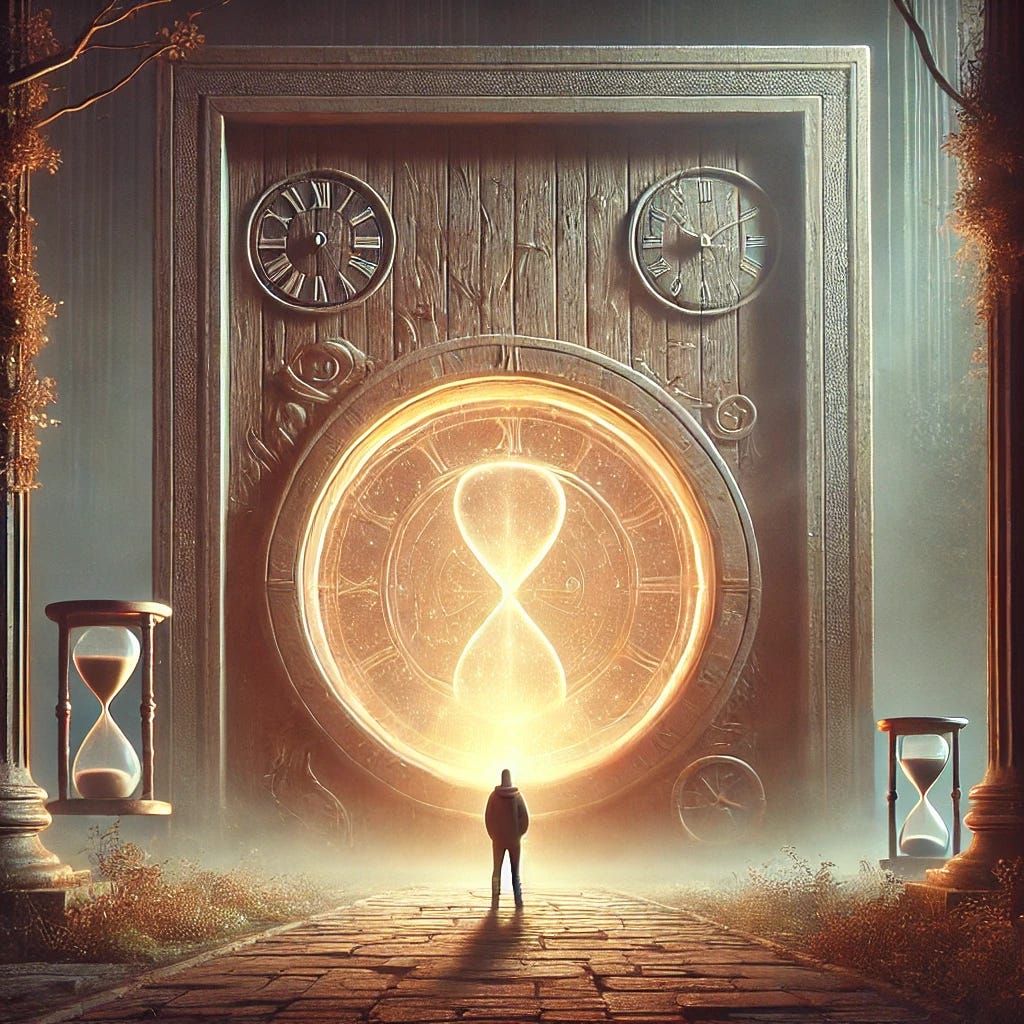

The poem starts with this simple image of standing outside a door. She's right there but can't bring herself to open it. Why? It's as if she's afraid of what or who might be on the other side. Maybe a stranger has replaced the familiar faces she once knew. That idea of coming home to find it no longer feels like home is a fear many of us can understand. On one occasion, I visited the home where I grew up and experienced a very similar feeling.

Then comes the moment of decision with her hand on the latch. It's such a small thing, right? Just open the door. But Dickinson makes it feel like it's too huge to do. It's as if opening that door means confronting her whole past and all the life changes she experienced since she left. And in the end, Dickenson can't do it. Instead of stepping inside, she runs away. The fact is that we cannot go home again because it's all in the past.

What's fascinating here is how she's more afraid of the door than of danger and the dead. That tells us this isn't just about a literal house. The house is a stand-in for something bigger. It could be her memories, her identity, or even the passage of time. She's not just scared of the house; she's scared of what it will make her feel.

This poem is a quiet but powerful exploration of what it means to face or avoid our past. It leaves us with the question: Would you open it if you were standing before that door? And if not, what might you be running from?

I did not run from the home where I grew up, but I felt overwhelming sadness about all the people who were no longer alive. Perhaps Dickenson was afraid of the ghosts of her past. I know I was.

I live five miles from my boyhood home. I had an idyllic childhood. When it comes to parents, I won the Powerball. So from time to time I drive past my childhood home and the neighborhood because it brings back so many sweet memories. In fact, this week I connected with the girl, now older woman, who grew up across the street. She had no siblings and we were like brother and sister.

When I visit my home I see the same bushes and shrubbery my Dad planted 77 years ago. He taught me how to use garden tools on those. They are still there is pristine condition as is the house because the people who have lived there for 33 years have taken such pride in it. I will continue to drive past every year or so because the connection I have to the house and neighborhood is warm, deep and everlasting.

The past is a luxury; I wonder how many can get there with clarity.

As a historian, I have the good fortune of positioning my past in a spectrum of narratives.

As a survivor of what is now finally being recognized by some to have been American fascism's proving ground, I was lucky to separate the delusional cultural vortex of anger and greed, from my own upbringing on the estuary, where the quantum was visible in every tide, season, and storm.

The door I cannot afford to walk through or past, the one between the road and the river, will always be there, until the whole estuary is underwater.

Yet, I do remember the sounds, colors, and lessons learned there, where Nature was the whole and infinite, and Culture was just a speck of it, not equal or seperate.